British Grand Strategy: Let’s You and Him Fight

In the 19th century, a term appeared in the English language to describe the rivalry between Great Britain and Russia in Central Asia - the Great Game. Although from a strictly historical point of view the term belongs to its era, we can apply it more broadly. For is not the relationship between countries, peoples and crowns on the world map precisely a Great Game in which everyone is looking for a place under the sun?

The English led the score in the Great Game in the 19th century, because they had a strategy, and their strategy worked. Britain's great advantage is that it is an island power. As such, it has no neighbors who can invade at any moment and who are natural rivals. Britain’s only concern is someone’s building a fleet comparable to Her Majesty’s - hence the concept of “the two-power standard” - i.e. Britain’s stated goal of having a navy stronger than the two next strongest world navies taken together.

Other famous world island powers are the Minoan civilization, Athens in its golden age, Japan and especially Venice, which was a world power during the Middle Ages. The English adore Venice and learned a lot from it. Americans, whose island is the size of a continent, learned from their English parents.

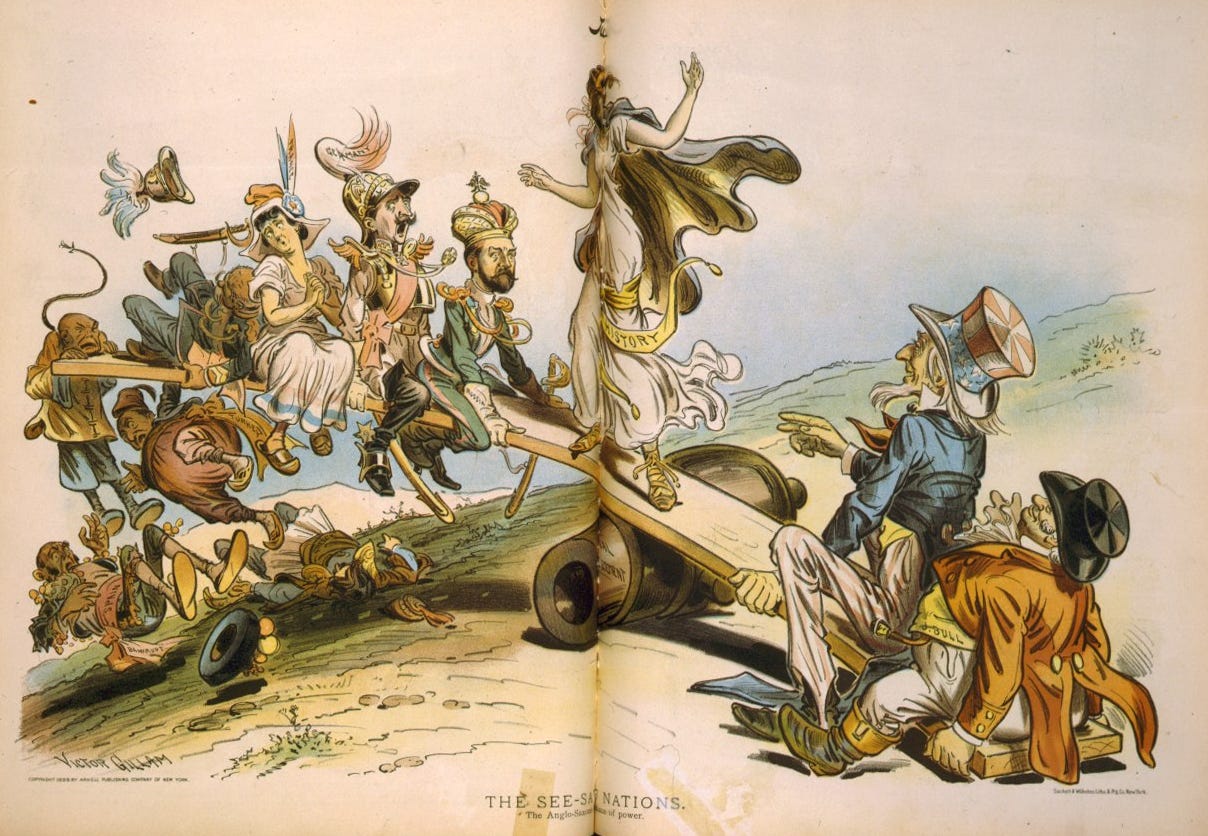

The insular advantage allows the British to practice the "let’s you and him fight" strategy. Always good at advertising, the British presented their idea to the Europeans as "the balance of power". In practice, this means the following. The British closely monitor the situation on the continent and at any moment try to support the second largest power on the continent against the first. The resulting war weakens both rivals. Others fight, the British win.

This approach is a major reason for the Albion’s reputation for perfidy. I suppose that only history and God can judge what is fair in love and war. Perfidious or not, the British built a powerful and fruitful culture and their (olden) ways merit careful study and frank admiration.

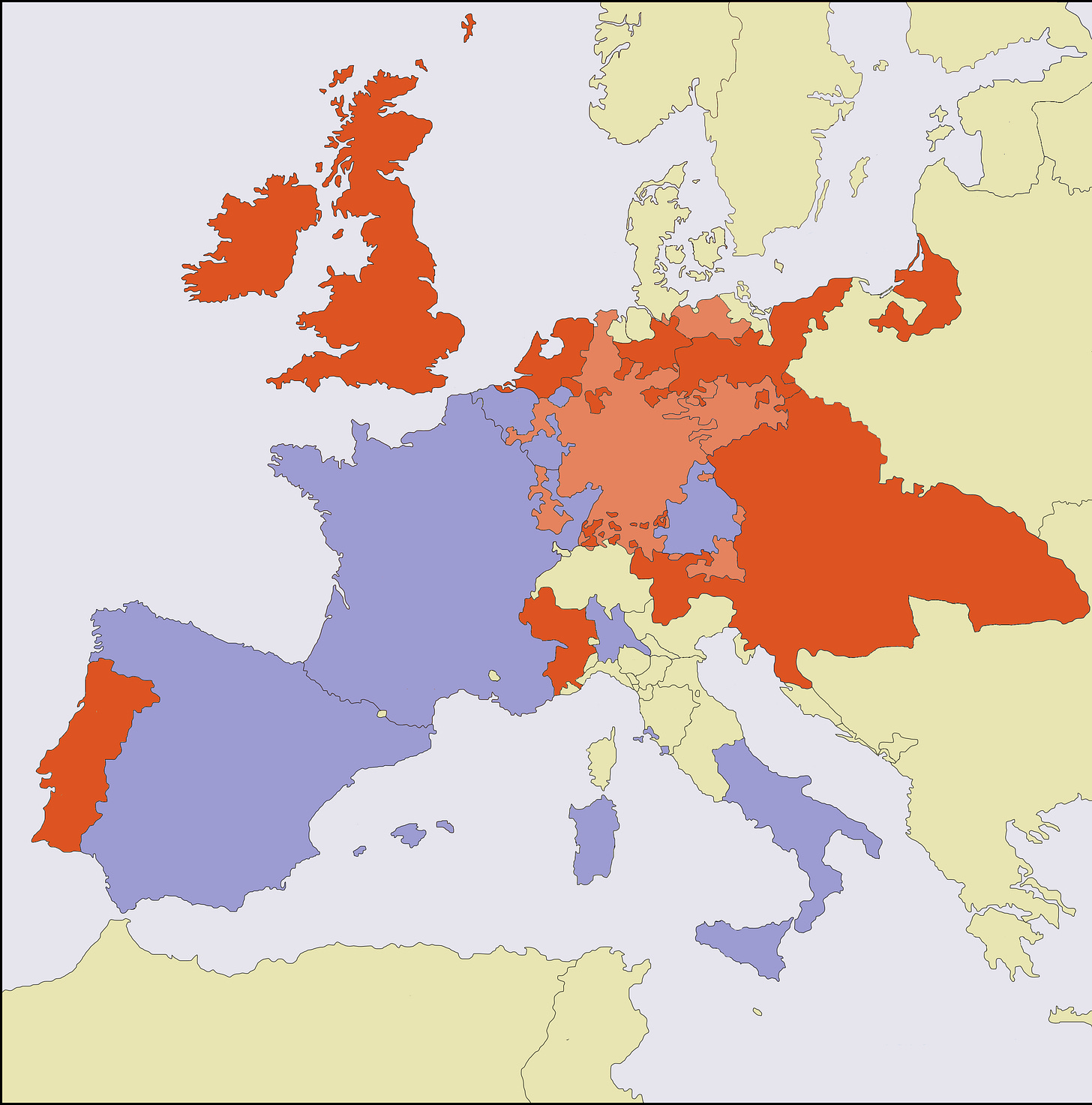

Between 1700 and 1815, the most powerful continental power was France. Consequently, the British organized four different coalitions against the French in four different wars. In the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1714), Britain and the Habsburgs fought France and Bavaria. Spain was the subject of dispute. The English, although still hesitant because of the relatively recent Glorious Revolution, achieved their goals.

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) pitted Great Britain, the Habsburg Empire (whose emperor was also Holy Roman Emperor at the time), Russia, and various smaller European powers against the French, supported by the Spanish (Britain's traditional oceanic rivals) and Prussia, hungry for a piece of the Habsburg possessions. The end of the war left the Habsburgs dissatisfied.

The next round was the particularly rough Seven Years' War (1756-1763), in which the Habsburgs allied themselves with France and Russia, and Britain with some German kingdoms and principalities, the strongest of which was Prussia. The British coalition won.

The struggle for supremacy finally ended with the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1789-1815), when the coalition of Russia and Great Britain broke continental Europe united by Napoleon. At the end of the war, the British defeated Napoleon at Waterloo (1815) and ended French supremacy on the old continent.

After its victory in the “First Patriotic War” (1812), despite the burning of Moscow, Russia was the only power in (continental) Europe that had not been defeated by Napoleon. This made her the number one target for the English, who quickly allied themselves with their until recently mortal enemies, the French. Another ally of Great Britain were the Turks, who stood between the Russians and their cherished goal - Constantinople. The natural result of these developments was the Crimean War (1853–1856), in which the British, the French, the proto-Italian kingdom of Piedmont, and the Turks allied themselves against the Russians and besieged Sevastopol. In a bad position, Moscow negotiated a truce at the cost of its right to a Black Sea fleet.

The British also made an unsuccessful attempt to divide America, supporting the South in the Civil War (1861-1865). After the failure, London modified its strategy to "if you can't beat them, join them".

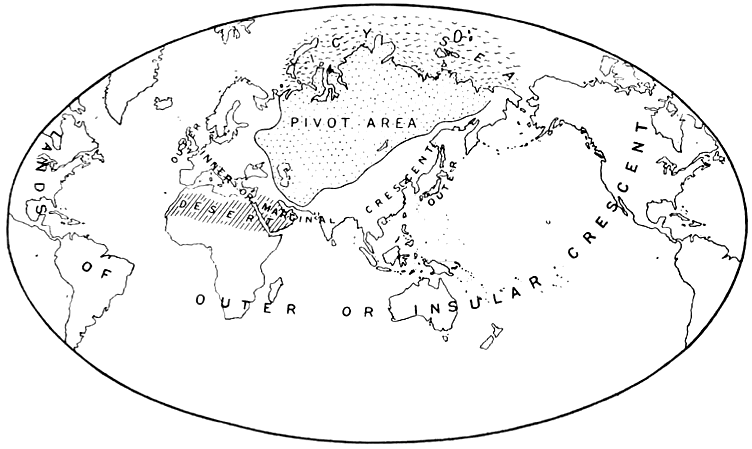

At the dawn of the 20th century, the English thinker Halford Mackinder (1861-1947) postulated a new English "grand" strategy, which generally consisted in sowing discord between the two great European powers of the period - Germany and Russia.

Mackinder's theory is worth quoting:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland;

who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island;

who rules the World-Island commands the world.— MacKinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality (1919), p. 150

The great threat to the Anglo-Americans, according to MacKinder, is an alliance between the Heartland of Europe (Germany) and the Eurasian Heartland (Russia).

I am not sure Mackinder is entirely correct; his theory seems to me a product of his time. But I think the following summary of the theory is useful: The Island Powers fear the alliance of the Continental Powers because it deprives the Island Powers of the ability to play "let’s you and him fight".

The British beat the Russians in 1905. This time another island power, Japan, did the dirty work. The Empire of the Rising Sun sunk the Russian fleet off Tsushima, thus ending the Russian naval threat to the British. Of course, this meant that the English crosshairs would move from St. Petersburg to Tokyo. Such are the inescapable rules of the Great Game.

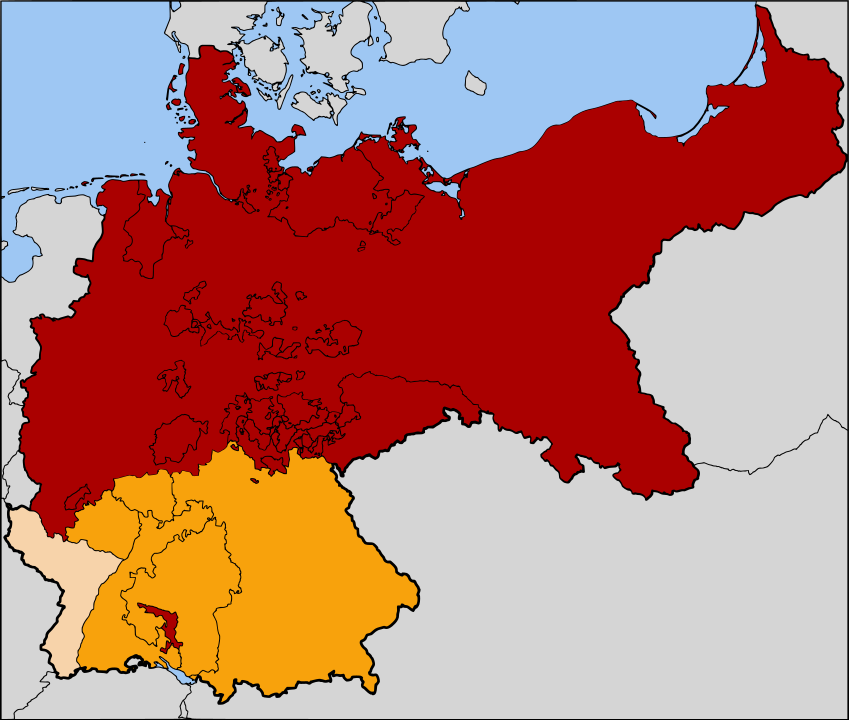

Meanwhile, Germany reunified after a decisive Prussian victory over France in 1870 (and before that against the Habsburgs in 1866) and successfully industrialized. The inevitable logic of the English "balance of power" strategy meant that the British would support France and Russia against Germany.

English machinations were thus one of the main causes of the disastrous period 1914-1945, in which Greater Germany (i.e. Germany plus Austria-Hungary) lost both world wars. In the second war, the Anglo-Americans used the opportunity to also deal with the Japanese problem and to secure dominance in the Pacific Ocean. Weakened by the two wars, the British passed the baton to their eager students the Americans, who originate from Great Britain, speak English and have an island the size of a continent.

In 1945, the USSR/Russia again became the main opponent. For some time there was no Great Power that could be used against the Russians. In 1972, Nixon did the right thing and visited China to try to win Beijing over to his side and away from the Russians’ “communist” sphere of influence.

After the Russians surrendered and lost both their empire and the Cold War (1946-1991), the Anglo-Americans were left with no real rivals and Fukuyama (1952-) declared "the end of history". Neo-conservative geeks set about taking over the last independent corners of the planet, and the Polish-American strategist Brzezinski (1928-2017) made plans to preserve American global supremacy and deal with Russia, which he politely describes as a "black hole." His book The Grand Chessboard (1997) contains the following insightful observations in Chapter 2:

In brief, for the United States, Eurasian geostrategy involves the purposeful management of geostrategically dynamic states and the careful handling of geopolitically catalytic states, in keeping with the twin interests of America in the short-term preservation of its unique global power and in the long-run transformation of it into increasingly institutionalized global cooperation. To put it in a terminology that hearkens back to the more brutal age of ancient empires, the three grand imperatives of imperial geostrategy are to prevent collusion and maintain security dependence among the vassals, to keep tributaries pliant and protected, and to keep the barbarians from coming together.

Ukraine, a new and important space on the Eurasian chessboard, is a geopolitical pivot because its very existence as an independent country helps to transform Russia. Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire. Russia without Ukraine can still strive for imperial status, but it would then become a predominantly Asian imperial state, more likely to be drawn into debilitating conflicts with aroused Central Asians, who would then be resentful of the loss of their recent independence and would be supported by their fellow Islamic states to the south. China would also be likely to oppose any restoration of Russian domination over Central Asia, given its increasing interest in the newly independent states there. However, if Moscow regains control over Ukraine, with its 52 million people and major resources as well as its access to the Black Sea, Russia automatically again regains the wherewithal to become a powerful imperial state, spanning Europe and Asia.

Despite its limited size and small population, Azerbaijan, with its vast energy resources, is also geopolitically critical. It is the cork in the bottle containing the riches of the Caspian Sea basin and Central Asia. The independence of the Central Asian states can be rendered nearly meaningless if Azerbaijan becomes fully subordinated to Moscow’s control. Azerbaijan’s own and very significant oil resources can also be subjected to Russian control, once Azerbaijan’s independence has been nullified. An independent Azerbaijan, linked to Western markets by pipelines that do not pass through Russian-controlled territory, also becomes a major avenue of access from the advanced and energy-consuming economies to the energy rich Central Asian republics. Almost as much as in the case of Ukraine, the future of Azerbaijan and Central Asia is also crucial in defining what Russia might or might not become.

A geostrategic issue of crucial importance is posed by China’s emergence as a major power. The most appealing outcome would be to co-opt a democratizing and free-marketing China into a larger Asian regional framework of cooperation. But suppose China does not democratize but continues to grow in economic and military power? A “Greater China” may be emerging, whatever the desires and calculations of its neighbors, and any effort to prevent that from happening could entail an intensifying conflict with China.

Hence, it becomes apparent that the war in Ukraine in 2022 is a direct and inevitable consequence of the collapse of the USSR. The logic of the Great Game and the age-old strategic imperatives of the Anglo-Americans doomed that territory to become a battlefield in the 21st century.

Separated from Russia, Ukraine could never survive. The Anglo-Americans, adept at manipulating others, would always turn Kiev against Moscow. The same logic obviously applies to Belorussia. Minsk has only survived Ukraine’s fate by willy-nilly going back into the fold.

Also notable are the concerns about the Chinese situation and the plans for a color revolution in Beijing.

In the book's chapter on the "black hole", Brzezinski proposes tying Russia to Europe. The idea is that Russians sacrifice their independence in exchange for an average European standard of living. But one of the complications in this case is that the rapprochement of Russia and Europe creates the risk of a Russo-German alliance, which is the biggest nightmare of the Anglo-Americans. The events surrounding the Nord Stream pipelines show the dilemma facing the Americans and the Germans. Berlin wants cheap Russian gas. And that's why they kept saying it was business, not politics, while they were building the pipeline. But although the Americans want Russia to function as a gas station for the Empire, they fear the good relations between Moscow and Berlin. This is how we got to the Nord Stream sabotage of September 2022.

The worst-case scenario for the American empire, according to Brzezinski, is what is happening right now.

Potentially, the most dangerous scenario would be a grand coalition of China, Russia, and perhaps Iran, an “antihegemonic” coalition united not by ideology but by complementary grievances. It would be reminiscent in scale and scope of the challenge once posed by the Sino-Soviet bloc, though this time China would likely be the leader and Russia the follower. Averting this contingency, however remote it may be, will require a display of U.S. geostrategic skill on the western, eastern, and southern perimeters of Eurasia simultaneously.

The Russians and Iranians have common interests in Syria and a ruthless common enemy. Therefore, the Russians are currently using cheap and effective Iranian unmanned kamikazes in Ukraine. Russian-Chinese relations can also be defined as at least "good". Whether an official coalition will be reached remains to be seen. But in fact, the interests of China, Russia, and Iran are currently converging.

So, at least by Brzezinski's criteria, American diplomacy over the past quarter century can be characterized as weak. What should they have done instead? Obviously, they should have pitted Russia (perhaps together with Europe or India) against China. Most likely, this scenario still remains the default plan, and the design of the current efforts at undermining Russia is to provoke a color revolution in Moscow that turns Russia into another imperial stooge to be used as cannon fodder.